Citation (Harvard): Ganchev, I. (2025) “Trump’s New Foreign Policy: Strategic Repositioning in a Multipolar World”, Regional Policy Insights, 3(1): 1-83.

Abstract:

In this paper, Dr. Ivo Ganchev builds on a lecture delivered in Mexico City to examine the strategic repositioning of U.S. foreign policy during the first 50 days of Donald Trump’s second term within the context of a shifting global order. While the U.S. remains the world’s most powerful actor, its role is evolving in response to China’s rise, the growing influence of middle powers, and structural changes in international politics. This paper explores how Trump’s approach prioritizes selective engagement, with a renewed focus on the Western hemisphere, alongside a relative shift away from Europe. It also contrasts U.S. and Chinese foreign policy strategies, highlighting China’s non-interventionist appeal to the Global South and its relatively predictable and stable foreign policy and international engagement strategy. The analysis considers whether Trump’s foreign policy represents a deliberate strategic shift or a reaction to global trends, ultimately arguing that the U.S. is adapting to multipolarity through a mix of economic, military, and diplomatic recalibrations.

Keywords: U.S. foreign policy, strategic repositioning, Trump, China, Global South, multipolarity, economic realignment, security, diplomacy, international relations.

Preface

This paper is based on a lecture delivered by Dr. Ivo Ganchev at the South Campus of Anáhuac University’s in Mexico City on 10 February 2025, at the kind invitation of Dr. Alina Gamboa Combs. The arguments and structure of the talk are adapted to provide a systematic analysis of the themes discussed. A video recording of the original lecture is available online on YouTube (URL).

Screenshot from a recording of Dr. Ivo Ganchev delivering the original lecture upon which this paper is based at Anáhuac University (Mexico City).

Dr. Ivo Ganchev (centre) with Dr. Alina Gamboa Combs (far right) and a group of students from Anáhuac University who interviewed him on Radio Anáhuac.

1. Introduction

Donald Trump’s return to the White House on January 20, 2025, has set in motion a recalibration of U.S. foreign policy. While the contours of this shift are becoming increasingly evident, it remains unclear whether these adjustments are guided by a coherent strategic vision or if they are largely reactive to evolving global conditions. Moreover, broader debates persist regarding the nature of the current international system—whether it is trending toward bipolarity, tripolarity, or a fully multipolar order. This uncertainty is reflected in the question mark at the end of this paper’s title: Trump’s Foreign Policy: Strategic Repositioning in a Multipolar World?

The paper seeks to address three key questions: (1) What are the observable manifestations of U.S. repositioning in terms of foreign policy during the first 50 days of Trump’s second term? (2) To what extent can strategic considerations explain shifts in U.S. foreign policy? (3) How do these shifts align with broader structural changes in international politics? Instead of speculating on the long-term trajectory of U.S. foreign policy, the analysis uses a structured approach to understand its current direction. The importance of the analysis in this paper stems from the centrality of the United States in global affairs since any change in its foreign policy has wide-ranging implications, not only for American allies and competitors but also for the international system at large.

One of the greatest challenges in analyzing foreign policy lies in distinguishing short-term political maneuvering from longer-term strategic realignment. The rapid pace of the news cycle often obscures underlying trends, making it difficult to separate momentary rhetoric from substantive policy shifts. Unlike media-driven narratives that focus on daily developments, an academic approach requires grounding analysis in theoretical frameworks and historical precedents. In this regard, a well-known joke in Beijing illustrates the difference between surface-level commentary and structured analysis: What distinguishes a professor from a taxi driver? Both closely follow current events, but the professor seeks patterns, while the driver reacts to headlines.

Foreign policy is shaped not only by leadership decisions but also by structural constraints. In his insightful book, Geopolitical Alpha: An Investment Framework for Predicting the Future, strategist Marko Papic (2020) rightly argues that state behavior is often dictated less by ideological convictions than by external limitations, such as economic pressures and power balances. Despite its global reach, the United States is not immune to such constraints. It must navigate the realities of a changing global order, where new centers of power—particularly China and key regional actors—are asserting greater influence. This reality underscores why the concept of multipolarity is critical in assessing U.S. foreign policy under Trump.

This paper argues that the United States is undergoing a fundamental foreign policy repositioning. Whether driven by a strategic blueprint or by ad hoc decision-making, this shift will likely result in a more selective approach to international engagement. As a consequence, Washington may find itself strengthening ties in certain regions while facing heightened resistance elsewhere. Rather than maintaining a uniform global presence, the U.S. appears poised to consolidate influence in select areas, notably in the Western hemisphere as well as potentially in the Indo-Pacific where economic and security interests are particularly pronounced.

While the paper is structured into 23 sections, its central arguments are organized around four broad themes, which are demarcated with Roman numerals. These themes are:

I. General Frameworks for Understanding U.S. Foreign Policy (Sections 2-4)

The sections under this theme introduce widely used frameworks and considerations that many analysts of international politics employ for interpreting shifts in American strategy.

II. Ongoing Shifts in Global Order and Their Structural Constraints (Sections 5-11)

The sections under this theme seek to explain the context in which evolving adjustments to U.S. foreign policy are taking place. As new geopolitical alignments emerge, the strategic environment within which the United States operates is shifting, redefining the constraints and opportunities that shape foreign policy choices. Here, the analysis focuses on the implications of ongoing transformations and their implications for Washington’s strategic calculus.

III. Foreign Policy under Trump 2.0: U.S. Strategic Repositioning? (Sections 12-17)

The sections under this theme analyze the nature of Trump’s approach to international affairs. His previous tenure was marked by a willingness to disrupt traditional alliances, renegotiate trade agreements, and recalibrate U.S. commitments abroad. The current trajectory raises key questions: Does this repositioning reflect a coherent strategic vision, or does it remain largely transactional and opportunistic? Is Trump’s foreign policy best understood as a calculated response to multipolarity, or is it shaped by domestic political imperatives and short-term economic considerations?

IV. Global Responses and Challenges to Trump’s New Foreign Policy (Sections 18-22)

The sections under this theme consider the reactions of international actors to Washington’s shifting priorities. While some allies have sought to align with U.S. objectives, others have responded with skepticism or resistance. This section also evaluates the challenges that Trump’s approach poses for the United States itself, particularly in terms of long-term diplomatic credibility and the sustainability of its foreign policy shifts.

The conclusion (Section 23) briefly reiterates the main argument of the paper and reflects on its broader implications.

A newspaper stand in London following Donald Trump’s election in November 2024. Right to use purchased by the Centre for Regional Integration.

I. General Frameworks for Understanding U.S. Foreign Policy

2. National Interest and the Foundations of U.S. Foreign Policy

A fundamental approach to analyzing U.S. foreign policy—under Trump or other any administration—is through the lens of national interest (Trubowitz, 1998; Morgenthau, 1982). The central question in this regard is: What objectives does the United States seek to achieve, and how does this overarching concept shape its engagement with the world? This question is particularly pertinent in light of recent statements made by key political figures, which provide insight into the evolving contours of U.S. strategic thinking.

Shortly before the original lecture upon which this paper is based, U.S. Senator Marco Rubio articulated a position that encapsulates a key aspect of contemporary American foreign policy discourse. Speaking on LiveNOW from Fox News (2025), Rubio addressed the role of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and, more broadly, the principle that should guide U.S. international engagement:

Why would we fund things that are against our national interest or don’t further our national interest, whether China is there or not? If China wants to waste their money on something that’s against their national interest, go ahead and do it. We’re not going to do it. It makes no sense for us to be involved in things that undermine what is important to America or that don’t further what is important to America, and irrespective of what China decides to do, this is taxpayer money. We shouldn’t be spending it on programs that have nothing to do with the United States and nothing to do with making America stronger, safer, and more prosperous. We have a foreign policy, and everything we do, including spending money, has to be aligned with that—has to further our national interest.

Rubio’s remarks reflect a recurrent theme in U.S. foreign policy rhetoric—the prioritization of national interest above all else. This naturally raises the question: What constitutes the national interest of the United States?

The definition of the U.S. national interest is neither static nor universally agreed upon. Historically, its interpretation has evolved in response to shifting geopolitical realities, economic imperatives, and domestic political considerations. While certain priorities—such as ensuring national security, maintaining economic prosperity, and preserving global influence—remain relatively consistent, the means by which these objectives are pursued fluctuate over time. The malleability of national interest underscores a key principle in foreign policy analysis (see, e.g., Weldes, 1999): a country’s national interest is not an objective reality but a construct shaped by leadership, ideological trends, and structural constraints.

United States Secretary of State Marco Rubio being interviewed on LiveNOW from Fox News on 4 February 2025.

Understanding how national interest is framed at different moments in history is crucial to interpreting U.S. foreign policy decisions. This aligns with broader discussions within international relations theory regarding the extent to which state behavior is driven by material realities as opposed to ideological commitments. Realist scholars, such as Steven Walt (2019) and John Mearsheimer (2018), emphasize that nationalism remains the dominant force in contemporary global politics, suggesting that foreign policy decisions—irrespective of their rhetorical justifications—are ultimately dictated by structural imperatives, resource constraints, and strategic incentives.

The realist perspective offers a useful lens for analyzing U.S. foreign policy under Trump. In democratic systems, policy legitimacy is derived primarily from domestic political dynamics—public opinion, political coalitions, and institutional support. No state operates in isolation; rather, foreign policy is the product of an ongoing negotiation between international imperatives and domestic constraints. Decision-makers must align their strategies with available resources, the geopolitical context, and the level of domestic support required to sustain long-term commitments. This dynamic is particularly evident in the U.S., where electoral cycles and shifting political coalitions exert significant influence on foreign policy priorities.

Thus, to make sense the trajectory of U.S. foreign policy under Trump, one must first examine how the United States perceives itself and its role in the world at this juncture. This self-perception is shaped not only by historical legacies but also by present-day domestic and international trends. The following section explores how these factors interact with the changing structure of the global order, delineating the constraints within which U.S. foreign policy operates.

3. The Four Traditions of U.S. Foreign Policy: A Framework for Analysis

One effective framework for analyzing U.S. foreign policy—both historically and in the contemporary context—can be found in Walter Russell Mead’s (2001) typology of American strategic traditions. In Special Providence: American Foreign Policy and How It Changed the World, Mead identifies four distinct schools of thought that have shaped the United States’ approach to international engagement: the Hamiltonian, Jeffersonian, Jacksonian, and Wilsonian traditions. Three of these traditions are named after U.S. presidents, and one Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton.

These four traditions do not operate in isolation; rather, they coexist and often compete for dominance in shaping foreign policy choices. Presidents and policymakers frequently draw upon multiple traditions, blending different strategic perspectives depending on political circumstances, public sentiment, and geopolitical realities. This framework provides a valuable analytical tool for understanding the approach of different administrations, including that of Donald Trump, whose foreign policy exhibits a strong Jacksonian influence with notable Jeffersonian elements.Since around 2017, there has also been a growing emphasis on encouraging Chinese companies to follow more environmentally sustainable practices. As relevant concerns have become more prominent on the global stage, the BRI has sought to incorporate “greening” its projects, aligning with global sustainability goals (Wang, 2021). This focus reflects China’s acknowledgment of the broader global conversation on climate change, but it also serves a strategic purpose for China—showing that it is contributing to the global public good and positioning itself as a responsible leader in sustainable development, which can lead to obtaining economic benefits as well.

A. The Hamiltonian Tradition: Commerce and Global Trade

The Hamiltonian tradition, which can be traced back to Founding Father and first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, prioritizes economic power as the foundation of national strength. It emphasizes the role of trade, industrial development, and financial institutions in ensuring U.S. prosperity and influence abroad. Hamiltonians advocate for a foreign policy that promotes open markets, protects commercial interests, and fosters strategic economic alliances. Historically, this approach has aligned with the priorities of major corporations, banking institutions, and proponents of globalization.

According to Mead (2001, p. 87), a “partial list of prominent Hamiltonians in American history would include Henry Clay; Daniel Webster; John Hay; Theodore Roosevelt; Henry Cabot Lodge Sr., who opposed Woodrow Wilson over the Treaty of Versailles; Dean Acheson; and the senior George Bush.” Among recent presidents, I would argue that Bill Clinton strongly embraced Hamiltonian ideals. Policies such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and U.S. support for international economic institutions reflected the belief that economic integration and free trade would advance American interests while consolidating its global leadership. However, I concede that there were also certain Wilsonian aspects to Clinton’s approach.

B. The Jeffersonian Tradition: Limited Foreign Entanglements

In contrast to the Hamiltonian vision, the Jeffersonian tradition—rooted in the foreign policy philosophy of Thomas Jefferson—emphasizes a cautious approach to international engagement. Jeffersonians prioritize the preservation of democracy and republican values at home, advocating for minimal foreign intervention and a restrained global footprint. While Jefferson himself oversaw major territorial expansion, his broader political philosophy centered on avoiding entangling alliances and ensuring that foreign engagements did not undermine domestic governance.

Historically, the Jeffersonian perspective has resonated with isolationist movements, libertarian factions, and political groups skeptical of extensive U.S. involvement in global conflicts. In earlier history, examples of presidents who epitomize this tradition include John Quincy Adams and James Monroe. But far more relevant to this paper, one can trace the influence of Jeffersonianism in Donald Trump’s “America First” approach, particularly in its emphasis on avoiding military interventions that do not directly serve core U.S. interests. The administration’s critique of longstanding alliances, withdrawal from certain multilateral agreements, and insistence on redefining burden-sharing arrangements within NATO illustrate the enduring influence of Jeffersonian thinking.

Beyond image-building, the BRI addresses critical economic and political goals. By 2013, China had built considerable capacity in sectors like construction, but as domestic demand began to slow, this raised concerns about potential unemployment and economic stagnation. The BRI became a strategic solution, channeling China’s excess capacity into international markets where demand for infrastructure existed (Cai et al., 2023). In doing so, it has provided Chinese companies with opportunities for international growth and mitigated domestic economic pressures by tapping into foreign markets.

C. The Jacksonian Tradition: National Honor and Military Strength

The Jacksonian tradition, named after President Andrew Jackson, is distinguished by its emphasis on national sovereignty, military strength, and the protection of American honor. This tradition views foreign policy primarily through the lens of national defense and self-interest, advocating for decisive military action when U.S. security or prestige is at stake. Jacksonian thinking is often associated with a strong belief in unilateralism, skepticism toward international institutions, and a preference for direct and forceful responses to perceived threats.

The best aligned early president with this tradition is William Henry Harrison. Until recently, it was difficult to identify many recent presidents who exemplify it clearly. However, even then its lasting legacy could still be traced in the thinking of contemporary senators and presidential candidates such as John McCain.

However, far more importantly in today’s politics, Donald Trump also aligns rather closely with Jacksonianism. His alignment with the long-standing Republican idea of “peace through strength” (The White House, 2025), along with emphasis on military readiness, withdrawal from multilateral agreements deemed disadvantageous, and prioritization of sovereignty over institutional diplomacy all reflect Jacksonian principles.

Trump’s rhetoric on strengthening the U.S. military, confronting adversaries through displays of power, and renegotiating economic and security arrangements to ensure a more favorable position for the United States exemplify this tradition. Additionally, Jacksonianism resonates with segments of the American electorate that favor assertive foreign policies and view international relations as a competitive, zero-sum arena (Chinoy et al., 2024).

While some critics have openly (and for good, albeit debatable reasons) pointed out that “Trump falls far short of the greatness and nobility of Jacksonianism” (White, 2020), it is hard to deny the empirically observable influence of this tradition on his approach. Plus, as Politico has reported, former Chief Strategist of the White House during Trump’s first term, Steve Bannon reportedly contacted Mead (presumably seeking an ideological ally), assuming he is a Jacksonian and was surprised to learn otherwise (Glasser, 2018). Although anecdotal, this episode gives direct proof that the influence of the long-standing traditions sometimes directly influence sitting presidents or their senior staff members.

D. The Wilsonian Tradition: Moral Responsibility and International Institutions

The Wilsonian tradition, rooted in the vision of President Woodrow Wilson, posits that the United States has a moral obligation to promote democracy, human rights, and global stability. Wilsonians advocate for active engagement in international institutions, believing that multilateral cooperation and global governance structures—such as the United Nations, NATO, and various diplomatic initiatives—are essential for maintaining world order.

Although it is difficult to identify presidents whose primary considerations stem mainly from Wilsonianism, the impact of this tradition can be seen across numerous administrations. For instance, post-World War II U.S. foreign policy, particularly under Franklin D. Roosevelt, reflected strong Wilsonian elements, as seen in the establishment of the Bretton Woods system and the United Nations. Jimmy Carter’s embrace of moralism and his embrace of human rights policies also falls in this tradition. More recently, to some extent the Obama administration’s emphasis on diplomatic engagement, coalition-building, and institutional solutions to global challenges also illustrated elements of Wilsonianism. Trump’s foreign policy de facto rejects this tradition, favoring bilateralism over multilateralism and national interests over global governance.

While from an intellectual perspective these four foreign policy traditions can be viewed as distinct perspectives, in practice they do not function in isolation. U.S. foreign policy is always shaped by a dynamic interplay between them, with policymakers often invoking multiple traditions to justify their decisions. For example, a leader advocating for military intervention might frame the decision in Jacksonian terms—emphasizing national security and deterrence—while simultaneously appealing to Wilsonian principles of democracy promotion. Similarly, a foreign policy that prioritizes economic diplomacy could be justified through both Hamiltonian arguments for trade expansion and Jeffersonian concerns for national economic self-sufficiency.

Trump’s foreign policy exhibits a clear mix of Jacksonian and Jeffersonian principles. The former include a strong emphasis on national strength, unilateral decision-making, and a transactional approach to international relations. The latter shape his skepticism toward long-term military commitments and alliances, particularly in his critiques of NATO, withdrawal from Afghanistan, and prioritization of economic over ideological considerations in foreign affairs.

Introducing this framework has broader value, as it offers readers a useful lens for analyzing both Trump’s foreign policy and the wider evolution of U.S. strategic thinking over time. The next section introduces another equally essential and broadly applicable framework.

4. The Influence of the Foreign Policy Community

Beyond the ideological traditions that inform U.S. foreign policy, it is also important to examine the key actors responsible for shaping it. While the executive branch, particularly the president, plays a decisive role in setting the overall direction of U.S. foreign policy, a broader network of policymakers, advisors, and institutional actors exerts significant influence over strategic decision-making. This network, often referred to as the foreign policy community, consists of individuals operating within government, academia, think tanks, and policy institutions. The composition and influence of this community contribute to both the continuity and constraints of U.S. foreign policy (Walt, 2018).

A defining feature of the U.S. policymaking system is the revolving door—a practice by which individuals transition between government positions, academic institutions, and private sector roles within the policy sphere (Spar et al., 1991; Van Apeldoorn and De Graaff, 2014). This dynamic fosters a high degree of continuity in U.S. foreign policy, as key decision-makers frequently remain within the same institutional ecosystem despite changes in political leadership. Similar practices exist in certain Latin American countries, where policymakers likewise move between government service and advisory roles in research institutions.

However, the close-knit nature of the foreign policy community also imposes pressures to conform. Graham Allison, in his seminal work Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis (1971), highlights a dynamic summarized by Steven Walt in his public lectures as “getting along to go along,” whereby individuals operating within a tightly integrated policy network often face implicit incentives to align with prevailing strategic paradigms. As a result, major shifts in U.S. foreign policy thinking tend to be gradual rather than abrupt, as alternative perspectives must first gain traction within elite policymaking circles before being institutionalized into mainstream discourse.

Despite this institutional inertia, recent years have witnessed the emergence of challenges to the previously dominant paradigm within the foreign policy establishment. A more conservative, Republican-aligned faction appears to be coalescing, advocating for a recalibration of U.S. global engagement. Whether this shift represents a lasting transformation or a temporary realignment remains uncertain. The traditional divide between neoconservatives and liberal internationalists continues to define much of the foreign policy debate, yet from an external perspective, the practical differences between these camps are often less pronounced than their rhetorical distinctions suggest. While neoconservatives frequently frame U.S. leadership in terms of American exceptionalism (Lipset, 1996; Walt, 2011), liberal internationalists emphasize the country’s role as an indispensable nation (Zenko, 2014; Lieber, 2022). Although these conceptual frameworks differ theoretically, the actual conduct of U.S. foreign policy has often followed a similar trajectory, with both schools of thought advocating for proactive international engagement (Tyrell, 2022).

A black pawn with a golden crown on the white square of a chessboard. Copyright-free image from Pixabay.

More broadly, the foreign policy community has historically maintained a strong consensus that the United States should play an active role in shaping global affairs rather than retreating into a status quo posture. This reflects deep-rooted structural imperatives rather than merely the ideological preferences of specific administrations. Regardless of partisan shifts in leadership, U.S. foreign policy has been consistently defined by a commitment to international engagement, military presence abroad, and economic leadership.

However, the global order is undergoing profound transformations, raising questions about whether U.S. policymakers have fully acknowledged or adapted to these shifts. As the next sections will explore, the evolving international system presents new constraints and opportunities that may challenge the entrenched assumptions of the foreign policy community, necessitating a reassessment of U.S. strategic priorities.

II. Ongoing Shifts in Global Order and Their Structural Constraints

5. The Rise of BRICS and the Changing Global Order

One of the most consequential developments in contemporary international relations is the rise of alternative power blocs, particularly BRICS[1] (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). The expansion of this bloc reflects an ongoing redistribution of global influence, challenging the long-standing economic and geopolitical dominance of the G7 (Mooradian, 2024). While the United States and its Western allies continue to exert considerable influence over global institutions, the increasing economic weight and political assertiveness of BRICS countries highlight a broader shift toward a more multipolar global order.

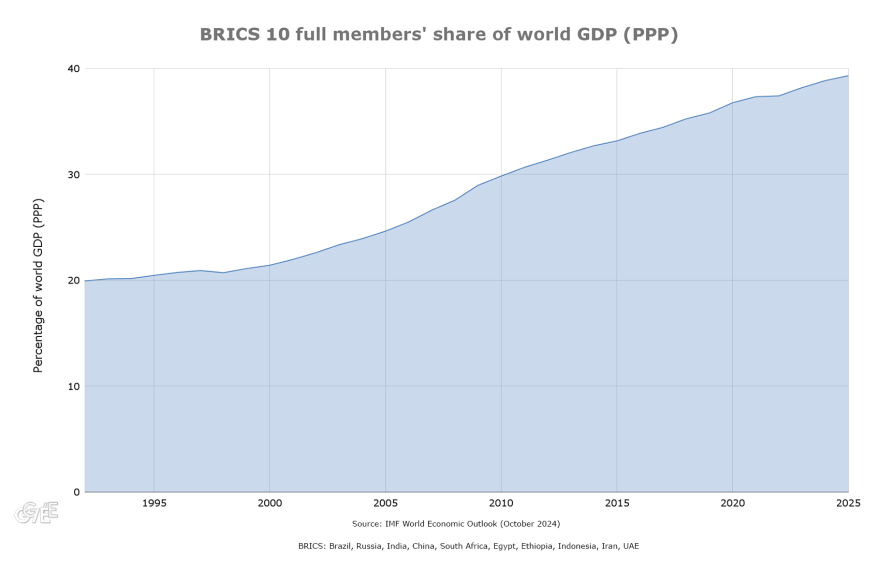

A key indicator of this shift is the growing economic clout of BRICS economies relative to the G7. Measured in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms, BRICS countries’ share of global GDP has risen steadily over the past three decades (Norton, 2025). Comparative studies suggest that economic influence is becoming more evenly distributed between traditional Western powers and emerging economies, a development that has significant implications for international trade, financial governance, and diplomatic alignments. The increasing importance of BRICS-led initiatives—such as the New Development Bank (NDB) and efforts to promote alternative trade mechanisms outside the dollar-based financial system—further illustrates the group’s evolving role in global affairs.

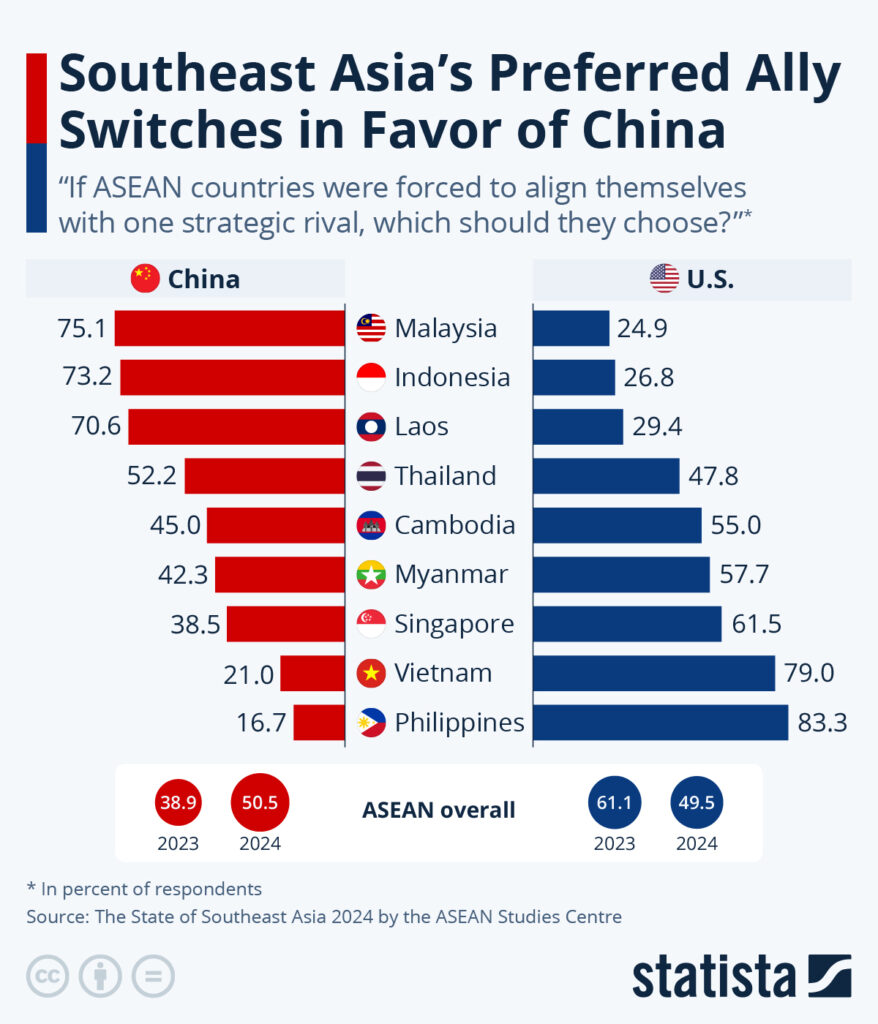

Beyond economic realignments, shifting geopolitical preferences underscore the changing nature of global influence. In key regions such as Southeast Asia, public opinion surveys reveal a near-even divide when respondents are asked whether they prefer closer alignment with the United States or China. Such findings suggest a growing ambivalence toward U.S. leadership in certain parts of the world, challenging long-standing assumptions about American primacy. The extent to which U.S. policymakers fully acknowledge these shifts remains a subject of debate.

Graph showing the rise of the BRICS members’ share of world GDP measured by PPP from 1990 to 2025. Image from Geopolitical Economy Report.

This mindset was evident during a recent panel discussion I attended in Singapore, where a U.S. government official asserted to his Singaporean counterpart before a large audience, “I know you guys prefer us, the Americans. I know you can’t say that.” The U.S. official’s assumption—namely that alignment with the United States remains the default preference when facing a choice where China is the other option—raises important questions about how American policymakers perceive their global standing. Rather than assuming inherent preference for U.S. leadership, it is necessary to consider the growing appeal of alternative partnerships, particularly with China and other BRICS members. As the widely cited graph below indicates (Buchholz, 2024), on average the split between China and the U.S. is quite even across Southeast Asia.

Graph showing a relatively even split between China and the U.S. among Southeast Asian states in terms of forming a preferred alliance with one strategic rival. Data from the ASEAN Studies Centre. Image from Statista.

This perspective reflects a broader challenge facing U.S. foreign policy: the persistence of outdated assumptions regarding global engagement. In the post-Cold War era, the United States operated within a largely unipolar framework, in which its economic, military, and institutional dominance was widely accepted as the foundation of the international system. However, as power distributions continue to evolve, such assumptions may no longer hold. A recalibration of U.S. strategic thinking will be necessary to adapt to the realities of a more contested international order. The following section will examine how these global shifts are constraining U.S. foreign policy and creating new challenges in an increasingly multipolar world.

6. Demographics and Technology

One of the most fundamental factors shaping global power shifts is the narrowing technological gap between the major players in the international system. Historically, technological superiority has been a decisive enabler of geopolitical dominance, allowing relatively small, technologically advanced powers to exert control over much larger populations (Innis, 1950; Postman, 1993; Diamond, 1999). During the colonial period and China’s Century of Humiliation, for example, European powers leveraged military, logistical, and industrial advantages to maintain influence over vast territories with relatively few personnel. However, this dynamic has changed considerably in the contemporary world, as access to advanced technology has become more widespread across multiple global actors.

While debates persist over whether the United States retains a technological edge over China in artificial intelligence (AI) and other frontier technologies, these discussions often obscure a more significant development: the gap between the two countries has narrowed so significantly that it no longer represents a decisive asymmetry in global power. Even if one state maintains a short-term advantage in a particular technological domain—such as a temporary lead in AI development—such marginal differences are unlikely to fundamentally alter the balance of power. Instead, long-term strategic influence is increasingly shaped by demographic and economic factors, particularly the size of populations that have access to comparable levels of technology.

A demographic analysis of global power shifts reveals clear structural trends:

• Asia accounts for approximately 60% of the world’s population (UNFPA, 2025), reinforcing its central role in global economic and geopolitical affairs.

• The BRICS bloc now represents nearly half of the world’s population, positioning it as a formidable counterweight to the traditional Western-led economic order.

• The United States and the European Union combined account for less than 10% of the world’s population. Even when including the entire Americas (North and South), the total still represents only around 22% of the global population.

These demographic realities have profound implications for the future distribution of economic and strategic influence. Markets, capital flows, and innovation potential are becoming increasingly concentrated in Asia, reinforcing its emergence as the global economic center of gravity. As economic and technological capabilities continue to diffuse beyond the West, traditional sources of U.S. dominance are being challenged by a more balanced and competitive international system.

China’s industrial and technological expansion exemplifies this demographic-driven shift in global power. In key sectors, Chinese firms are increasingly outperforming their American counterparts, illustrating the broader economic realignment underway.

One case in point is the EV industry, where China is poised to outperform the U.S. in the coming years. While Tesla remains a dominant player in the sector, its long-term stability is closely tied to the strategic priorities of its owner, Elon Musk, whose business interests span industries as diverse as space exploration (SpaceX), satellite communications (Starlink), and AI (xAI). Musk’s potential shifts in focus introduce uncertainties into Tesla’s future trajectory. In contrast, Chinese automakers such as BYD operate within a more stable and strategically coordinated industrial ecosystem (Bloomberg, 2025). Supported by comprehensive supply chains, a dedicated labor force, and national industrial policies that reinforce competitiveness, Chinese EV manufacturers are positioned for sustained long-term growth.

Beyond the EV sector, China’s industrial ecosystem has outpaced many Western economies in terms of scale, efficiency, and technological integration. The country’s commitment to industrial development, supported by government policies prioritizing advanced manufacturing, has enabled Chinese firms to surpass many of their Western counterparts in production capacity, supply chain resilience, and cost efficiency. Unlike many U.S. corporations that outsource significant portions of their manufacturing to third-party contractors (Collins, 2021), Chinese firms have maintained control over extensive production networks, reducing vulnerability to external supply chain disruptions (Baldwin, 2024). This convergence of demographic mass and technological capacity—currently in China but over time in Asia and other developing regions at large—signals a reconfiguration of structural power in the international system. The next section examines the strategic blind spots that may result from underestimating these shifts.

7. Blind Spots in Mainstream U.S. Discourse

Despite significant structural shifts in the global order, U.S. policymakers have yet to fully internalize the broader implications of these changes. Discussions about China in American political and media circles often focus on specific technological competitions—such as advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and semiconductor supply chains (e.g., Murgla et al., 2025; King and Wu, 2025). While these issues are relevant, they fail to capture the depth and breadth of China’s industrial transformation or the demographic and economic forces that are reshaping global power distributions.

A key risk for U.S. foreign policy lies in its tendency to frame global competition through a narrow technological lens rather than recognizing the fundamental realignment occurring across multiple domains, including industrial capacity, infrastructure investment, and trade influence. While Washington remains preoccupied with sector-specific rivalries, emerging economies continue to strengthen their strategic positions, shifting the balance of power across multiple domains, not limited to any single technological contest. Adapting U.S. strategic thinking to acknowledge these broader transformations will be crucial for maintaining influence in an increasingly multipolar world.

One of the most significant challenges in contemporary U.S. foreign policy is a reluctance to fully acknowledge the changing world order. In my view, mainstream media narratives in the United States often present China and other rising economies through a selective or overly simplistic lens (e.g., Gan, 2024), indirectly feeding outdated assumptions about American global primacy. Rather than engaging with the complexity of economic and political transformations taking place in the Global South, U.S. discussions frequently focus on issues that fit into pre-existing geopolitical frameworks, such as military tensions in the South China Sea or concerns about technological competition.

This selective framing has produced significant blind spots in U.S. foreign policy discourse. For example, despite having a population comparable to that of the United States, growing rapidly and recently entering BRICS, Indonesia has been largely absent from U.S. strategic discourse. As this country, and many like it, continue to rise, their influence in global markets and regional diplomacy will grow substantially (Koenen and Simpfendorfer, 2024). This trend reflects a broader pattern in which emerging economies are asserting themselves on the world stage in ways that are not always adequately reflected in U.S. policymaking circles.

Similar patterns can be observed in Latin America and Africa, where governments are increasingly adopting flexible and pragmatic foreign policy approaches. Rather than aligning with any single global power, states in these regions are engaging with multiple partners—including China—based on economic and strategic interests rather than ideological loyalty (Kalout and de Sá Guimarães, 2022; Sun, 2025; Ferchen, 2022). This represents a fundamental shift from Cold War-era alignment dynamics and suggests that U.S. policymakers must move beyond assumptions of default alignment with the West.

Beyond economic and strategic shifts, another long-term transformation that remains insufficiently recognized in U.S. policy circles is the gradual decline of American cultural dominance. While the United States remains a key player in global media and entertainment, cultural globalization is increasingly reducing its once-unrivaled influence. The rise of non-Western entertainment industries—exemplified by the growing popularity of K-pop (Adams, 2022), J-pop (Stassen, 2024), and Indian cinema (Jones, 2014)—illustrates a diversification of global cultural preferences. Streaming platforms such as Netflix, which once primarily showcased U.S. productions, now feature a far more international selection of content, reflecting broader shifts in global cultural consumption.

This dispersion of cultural influence is likely to accelerate as AI-driven real-time translation technologies continue to break down language barriers. Future generations of political leaders and global decision-makers are growing up in a world where cultural influences are no longer unidirectionally shaped by American media. Since they grew up in a world shaped largely by American media dominance, previous generations generally respected the global reach and innovation of U.S. culture—even if they did not always admire it. In contrast, the next generation is emerging in a more culturally decentralized world. This shift may erode the implicit normative preference for engagement with the United States that previous generations of global elites often held.

While cultural transformations do not have the same immediate geopolitical impact as industrial or technological shifts (Anandakumar, 2024), they contribute to the broader diffusion of influence that characterizes an emerging multipolar world. The assumption that American culture remains uniquely aspirational in global politics may become increasingly outdated, reinforcing the need for U.S. policymakers to reassess how the country positions itself within the evolving international order.

These shifts—technological, demographic, and industrial—suggest that the United States can no longer assume uncontested global leadership. While it remains an influential power, the structure of global politics is increasingly multipolar, with rising powers playing a more decisive role in shaping international economic and strategic landscapes.For U.S. foreign policy to remain effective, it must move beyond outdated assumptions and engage with these changing realities in a more nuanced manner. Rather than relying on selective media narratives that reinforce pre-existing strategic outlooks, policymakers must adopt a broader perspective that takes into account demographic trends, industrial realignments, and the evolving geopolitical preferences of emerging economies. Failing to do so risks leaving the United States strategically unprepared for a global order where power and influence are more evenly distributed than in the past.

8. Structural Implications of the Changing Global Order

The ongoing shifts in global power dynamics carry profound structural implications for the international system. Scholars of international relations have long debated the nature of international order, exploring concepts such as anarchy, hierarchy, and the distribution of power within the system (Lake, 1996; Nedal and Nexon, 2019; Ganchev, 2022). Today, the central question is: What kind of international system is emerging?

The answer remains contested. Competing perspectives suggest that the world is evolving toward bipolarity, tripolarity, multipolarity (for a comparison of these systems, see Waltz, 1979, pp. 129-138), or as I contend—a hybrid structure that incorporates elements of all three, which may persist for the foreseeable future. No matter where one stands in this debate, understanding these structural possibilities is essential for analyzing the strategic realignments taking place in global affairs and for assessing how U.S. foreign policy should adapt to these changing realities. This structural analysis draws from neorealist interpretations, which emphasize the distribution of material capabilities, it also leaves room for constructivist insights on how ideas, identities, and perceptions shape how states respond to these shifts.

A. Bipolarity: The U.S.-China Rivalry

One of the most prevalent arguments among scholars and policymakers is that the international system is moving toward a new bipolar order, with the United States and China as the two dominant poles (Kupchan, 2021; Maher, 2018). This perspective draws historical parallels to the Cold War but acknowledges key differences. Unlike the U.S.-Soviet competition, where the two blocs were largely isolated from each other, the U.S. and China remain deeply integrated into the global economy. The extensive economic interdependence between the two powers makes outright decoupling unlikely or impractical, limiting the extent to which a strict bipolar system can emerge.

Nevertheless, key characteristics of a bipolar system—such as intensified strategic competition, military build-ups, and the formation of rival economic and security networks—are becoming increasingly visible. U.S. efforts to counter China’s rise, including the Indo-Pacific strategy and semiconductor export restrictions, suggest a containment dynamic reminiscent of Cold War-era strategic thinking. However, the globalized nature of trade, finance, and technological supply chains complicates efforts to establish clear spheres of influence.

B. Tripolarity: The U.S., China, and Russia as Key Actors

An alternative perspective suggests that the world is best understood as tripolar, with three primary actors—the United States, China, and Russia—dominating the global security landscape (de la Cal, 2025; Asmolov and Babaev, 2024). This model focuses on military power and energy resources as defining pillars of influence.

• While China and the U.S. dominate the economic domain, Russia’s military and energy resources position it as a global actor despite its economic weaknesses.

• The war in Ukraine has reaffirmed Russia’s disruptive capacity in global security dynamics, even amid sanctions.

• Russia’s energy leverage, particularly in Europe and Asia, reinforces its position as a distinct pole within the system.

While the tripolar model captures important security dynamics, its main limitation lies in Russia’s relative economic decline compared to China and the U.S. Over time, Russia’s global role may increasingly depend on its strategic partnerships, particularly with China, rather than on independent economic or technological prowess.

C. Multipolarity: The Dispersion of Global Influence

A third perspective posits that the international system is shifting toward multipolarity, characterized by a more distributed balance of power (Ashford and Cooper, 2023; Pierini, 2024). Under this model, influence is no longer concentrated in Washington and Beijing but is instead diffused across a range of major and middle powers.

Key actors in a multipolar system include:

• The United States and China as the two dominant global powers.

• Russia as a major military power with significant influence in Eurasian security.

• The European Union as an economic powerhouse, wielding considerable regulatory and financial influence despite lacking a unified defense policy or integrated military capability.

• India as an increasingly assertive strategic player, expanding its global footprint in economic and security affairs.

• Middle powers such as Brazil, Turkey, and South Africa, which exert growing influence in regional affairs and global governance.

This model highlights the growing agency of emerging economies and regional actors, suggesting that future geopolitical competition will not be strictly limited to a U.S.-China rivalry but will involve a more complex array of strategic interactions among multiple global players.

D. Hybrid Models: Bipolarity Within a Multipolar Framework

Some scholars propose a hybrid structure, blending elements of both bipolarity and multipolarity. For instance, Kishore Mahbubani (2024) describes the current system as a “bipolar world in a multipolar sea”, arguing that while the U.S. and China dominate global geopolitics, numerous other actors exert significant influence in shaping the international system (Asia Society, 2024).

I have previously articulated a similar view to my colleagues in Beijing, playfully using terminology familiar in Chinese political discourse—“bipolarity with multipolar characteristics[2]”. This phrasing reflects the reality that while the U.S.-China rivalry remains the defining feature of global affairs, the agency of secondary powers cannot be ignored.

Regardless of the exact terminology one uses, the core insight remains the same: while two dominant superpowers are engaged in strategic competition, the broader international system is shaped by a diverse range of actors whose influence cannot be dismissed. The key challenge for U.S. foreign policy, therefore, is to recognize and engage effectively with this complex and evolving geopolitical landscape, rather than viewing the world solely through the binary lens of great-power competition.

E. Implications for U.S. Foreign Policy

The structural shifts outlined above present significant challenges for U.S. policymakers. If the world is indeed becoming more multipolar, Washington can no longer rely on traditional Cold War-style strategies of containment and bloc-based competition. Instead, the United States must develop a more flexible, nuanced approach to diplomacy, economic engagement, and security cooperation.

Key strategic imperatives for U.S. foreign policy in this evolving order include:

• Recognizing the importance of middle powers: Countries such as India, Brazil, and Turkey will play increasingly independent roles in global affairs, and U.S. policy must account for their strategic autonomy.

• Adapting to economic multipolarity: The rise of BRICS and other economic coalitions suggests that Washington must engage proactively with a broader set of actors beyond its traditional transatlantic alliances

• Balancing competition with cooperation: While rivalry with China will remain a key feature of U.S. foreign policy, areas of mutual interest—such as climate change, global health, and financial stability—require engagement beyond zero-sum competition.

• Avoiding outdated assumptions: U.S. policymakers must move beyond Cold War-era frameworks and acknowledge the strategic complexity of a world where power is increasingly distributed

As the next section will explore, the constraints imposed by this evolving structural order will shape the effectiveness of U.S. foreign policy and ultimately determine the degree to which it can sustain its global leadership in the coming decades.

9. Implications of the Structural Transition

The transition toward a new global order carries profound consequences across security, economic, financial, governance, and ideological dimensions. These changes are not occurring in isolation but are deeply interconnected, shaping how states engage with one another and recalibrating global power structures.

A. Security Implications

As global alignments shift, traditional alliances are being redefined to reflect the evolving geopolitical landscape. The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad)—comprising the United States, India, Japan, and Australia—has gained increased prominence as a strategic counterweight to China’s influence in the Indo-Pacific (Kersten and Yoon, 2024). Similarly, NATO’s future remains secure, but questions regarding burden-sharing and strategic priorities persist as European members reassess financial contributions and defense commitments.

Military competition is also entering a new phase, driven by technological advancements that are redefining warfare. The ongoing conflict in Ukraine has underscored the role of drone warfare, cybersecurity, space-based defense systems, and AI-driven military capabilities in shaping modern conflict dynamics (Williams and Brawley, 2025). These developments suggest that future security challenges will not be dictated solely by conventional military power but by technological superiority and adaptability.

B. Economic and Trade Transformations

Global trade patterns are shifting from an open, integrated system toward a more fragmented order centered around regional economic blocs. Asia, particularly China, has become the primary driver of this transformation, while Africa and Latin America are also consolidating stronger economic identities. The African Union’s increasing influence in global governance (Hadj Arab, 2024) reflects this shift, as African nations assert greater autonomy in economic and political decision-making.

Although it has become less central recently, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and its effect on global trade is also a critical element, representing one of the most ambitious infrastructure projects in modern history. With extensive investments in connectivity and supply chains, the BRI has reconfigured economic alignments, particularly in the Global South. While its long-term impact remains debated, its role in shaping the global economy is undeniable.

There has been a shift from BRI “1.0” to “2.0” in terms of introducing more stringent monitoring when it comes to providing funding for projects and focusing on more sustainable ventures (Stanhope, 2023). This will have qualitative implications for the initiative’s effect, but will not undo its foundational impact on global trade and infrastructure. Besides, China’s recently introduced Global Development Initiative (GDI), Global Security Initiative (GSI), and Global Civilisation Initiative (GCI), are evidence that the country will continue to engage and provide new contributions to the global community, in line with its evolving vision for global engagement (Ganchev, 2024).

C. Financial System and Currency Shifts

The long-standing dominance of the U.S. dollar in global finance is being gradually challenged by alternative financial systems. While the dollar remains the world’s primary reserve currency, rising use of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), particularly China’s digital yuan, signals an attempt to diversify international transactions away from U.S. financial mechanisms (Orcutt, 2023; Bai et al., 2025). In parallel, an increasing number of cross-border transactions are now conducted in yuan, rubles, and other non-dollar currencies, suggesting a slow but steady shift toward a more multipolar financial system. This does not imply an imminent displacement of the dollar, but it does indicate an ongoing erosion of its unrivaled hegemony. As emerging economies develop their own financial frameworks, the traditional U.S.-centric monetary order will likely face new pressures and constraints.

D. Governance and Institutional Challenges

Multilateral institutions such as the United Nations, World Trade Organization (WTO), and International Monetary Fund (IMF) are facing growing challenges to their authority (Torres, 2022). Countries in the Global South have increasingly pushed for a more equitable governance structure, questioning the legitimacy of institutions that remain largely shaped by Western priorities. As decision-making within these bodies becomes more contested, the ability of traditional global governance mechanisms to enforce policies may weaken, necessitating reforms to accommodate a more diverse set of international stakeholders.

E. Ideological and Normative Shifts

The post-Cold War assumption that Western democratic models would continue expanding globally has weakened, as many countries have adopted governance structures that prioritize state sovereignty, economic development, and political stability over liberal democratic norms. While the U.S. and its allies continue to advocate for democratic values, this narrative is increasingly being challenged by alternative governance models that emphasize state-led development and non-interventionist policies (Barnes-Dacey and Shapiro, 2023; BBC, 2021).

Beyond formal governance structures, a more subtle transformation is taking place in the realm of cultural and ideological influence. As mentioned before, the relative dominance of U.S. cultural power is diminishing as globalization fosters a more pluralistic exchange of cultural narratives. This reflects a broader trend in which American soft power is no longer unchallenged, particularly among younger generations worldwide.

The structural transformation of the world order is no longer a theoretical projection but an ongoing reality. The traditional U.S.-led global order is giving way to a more complex and decentralized system, whether best described as bipolar, tripolar, or multipolar. This transition carries profound implications:

• Security alliances are being recalibrated as countries reassess their strategic partnerships.

• Trade and economic systems are becoming regionalized, reducing the dominance of a single, unified global framework.

• Financial transactions are diversifying, gradually eroding U.S. dollar hegemony.

• Governance institutions are facing strain, as emerging powers demand greater representation.

• Normative debates over governance are intensifying, with no single ideological model dominating the international sphere.

Adapting to this shifting landscape requires U.S. policymakers to move beyond outdated assumptions of uncontested global leadership. The rise of new economic and political power centers demands a more adaptable, inclusive, and strategically nuanced approach to international engagement. The extent to which the United States successfully navigates this transition will determine its ability to retain influence in an increasingly complex and competitive world.

Multiple inter-connected pieces on a world map. Copyright-free image by Karyme França from Pexels.

10. Convergence of Political-Economic Models: Beyond the Democracy vs. Autocracy Divide

One of the dominant narratives in Western discourse on global politics is the binary competition between democracy and autocracy, often framed as a contest between liberal and authoritarian governance models. This perspective, while influential, oversimplifies the evolving nature of political and economic systems in the 21st century. Rather than adhering to a strict dichotomy, many states are adopting hybrid approaches that blend elements of both market-driven capitalism and strategic state intervention.

This emerging convergence aligns with the concept of a “third way,” a notion that Zbigniew Brzezinski and Samuel Huntington (1964), among other scholars, initially introduced. Although Brzezinski remained skeptical of this notion (see, e.g., FreeMediaOnline, 2018), it seems to me that this has been happening for the past two or three decades. The convergence argument challenges the rigid separation between democratic capitalism and authoritarian state control. In practice, governments across various political systems—whether democratic or non-democratic—are playing an increasingly active role in economic development, industrial policy, and foreign policy coordination. This trend raises important questions about the validity of the traditional ideological divide and suggests a more complex and adaptive model of governance.

A common misconception in Western analysis is that China functions as a monolithic, centrally controlled state with little internal variation or debate (Lenz, 2023). In reality, China’s political and economic landscape is shaped by a diverse set of actors, institutional dynamics, and competing interests. Understanding these complexities is crucial for assessing the extent to which China’s governance model differs from—or converges with—Western economic approaches.

While China’s central government sets national priorities, local governments operate with a significant degree of autonomy, often pursuing policies that reflect regional economic conditions rather than strict adherence to national directives (Lin et al., 2006). Fiscal constraints contribute to this decentralization; many local governments are at times underfunded relative to their policy responsibilities, leading to varied economic strategies across different provinces. These dynamics highlight the limitations of viewing China as a purely top-down, centrally planned system.

Contrary to simplistic depictions of the Chinese system as one where the Communist Party fully directs state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to serve political purposes, many of them spend the bulk of their time and effort chasing financial targets to maintain good levels of profitability.

This pattern has persisted for nearly two decades, but has only recently gained recognition in academic literature (Hawes, 2023). Besides, it is well-known that the Chinese private sector plays a crucial role in global supply chains. Many of the world’s leading consumer and technology products—from smartphones to high-tech manufacturing components—are produced by private Chinese firms which are forced to work at thin margins since they operate in a highly competitive environment. In other words, China’s model is driven by economic pragmatism where efficiency is a central concern.

Moreover, while China is often characterized as an interventionist economy, many Western economies have continuously adopted state-driven policies in key sectors, challenging the notion that free-market capitalism operates without government intervention.

• In the United States, the CHIPS and Science Act (2022) represents a major industrial policy initiative aimed at bolstering domestic semiconductor production—an explicit state effort to reshape global supply chains.

• The European Union’s agricultural subsidies, which direct significant public funds to sustain domestic agriculture (European Parliamentary Research Service, 2022), illustrate another form of state-driven economic intervention.

• Infrastructure spending, technology funding, and direct industry support programs are increasingly shaping Western economic strategies, mirroring practices traditionally associated with state-led economies.

In other words, I argue that the view—favored by many Western analysts—which posits there is a strict competition between opposing “ideal” “democratic”/“capitalist” vs. “authoritarian”/“communist” models (e.g., Beckley and Brands, 2023), is not only highly inaccurate but also misleading as it perpetuates an abstract debate that is fundamentally detached from the political realities of the contemporary world. In my view, a global trend is emerging in which states across different governance systems are adopting targeted economic interventions to enhance industrial growth, national competitiveness, and geopolitical influence. Hence, any meaningful discussion must move beyond the oversimplified dichotomy still prevalent in much of the media and academic discourse.

As these structural transformations unfold, the international system is experiencing heightened instability and competition. However, this does not necessarily imply an inevitable escalation into large-scale conflict. Instead, the emerging world order is likely to be characterized by: a) greater uncertainty regarding which powers will dominate in different regions; and b) a decentralized global structure in which multiple spheres of influence emerge, rather than a single dominant hierarchy.

These developments raise an important, thought-provoking question: If the traditional models of bipolarity, tripolarity, or multipolarity do not fully capture the complexities of the current system, are there alternative ways to conceptualize the emerging global order? The section introduces a historically-minded framework for understanding the geopolitical landscape, and then extrapolates it to explain the current realities of international politics.

11. Role Specialization in the Global System: The 19th Century Model

An alternative way to conceptualize world order—beyond the traditional frameworks of bipolarity, tripolarity, or multipolarity—is through the idea of role specialization among states. Rather than focusing solely on rankings of power, this perspective examines how different nations contribute uniquely to global governance, security, and economic development.

In an examination of the 19th-century European international system, Schroeder argued that global stability was not simply maintained by a balance of power but by the distinct functions that major states performed. Instead of competing across all domains, nations assumed specialized roles that shaped the broader system’s equilibrium. This historical perspective offers a useful framework for understanding contemporary global politics, where major powers do not necessarily engage in direct competition in all fields but instead carve out strategic niches within the international system.

During the 19th century, European powers played distinct roles that contributed to systemic stability, which are exemplified in this long section quoted from Schroeder (1994, pp. 126-127):

Britain, for example, claimed during this period and others to be the special holder of the European balance, protecting small states, promoting constitutional liberty, encouraging commerce, and preserving peace.

Russia claimed to be the guardian of the monarchical order in Europe, defender of all states against revolution, and protector especially of smaller states against threats or domination by other great powers.

The United Netherlands after 1815 claimed special treatment, and after 1830 Belgium claimed guaranteed neutrality, because the Low Countries served Britain and others as a barrier against French expansion, and served Austria, Prussia, and the lesser German states as a vital economic and political link connecting Britain to the Continent and Central Europe, curbing its drift toward isolation and preoccupation with its empire.

Switzerland had special functions as a neutral state under joint European guarantee, which were both strategic-to keep the passes between Germany and Italy out of any one great power’s control – and broadly political – to make France, Austria, and Germany jointly responsible for a crucial area.

Denmark and Sweden undertook roles as neutrals guarding the entrance to the Baltic, thus serving everyone’s commercial interests and preventing the constant struggles over the region from 1558 to 1815 from flaring up again.

The Papal State functioned as the political base for the Pope’s independent reign as head of the Catholic church, which was considered vital by many states, including Protestant ones, to prevent international struggles over control of the church and religion.

The Ottoman Empire played roles both strategic-keeping the Turkish Straits and other vital areas out of great-power hands-and political-buffering against possible Austro-Russian clashes over influence in the Balkans, or Anglo-Russian conflict over the routes to India.

The smaller German powers played roles as independent states in forestalling struggles between Austria or Prussia for control of Germany, or attempts by France or Russia to dominate it from the flanks; as well as buffers and decompression zones between the absolutist East and the liberal-constitutionalist West.

Many special international functions were assigned to the German Confederation from 1815 on: regulating and controlling conflicts between individual German states, between estates and princes within individual states, between the Confederation and the individual states, between Protestants and Catholics, and between the great powers Austria and Prussia, former bitter rivals for supremacy in Germany and now required to work together to manage the Confederation.

Any historian knowledgeable in this area could extend this list.

While today’s world is no longer Eurocentric (Hobson, 2012), many states continue to differentiate their roles within the global system rather than competing across all dimensions. Instead of viewing international politics as a straightforward power struggle between dominant poles, role specialization suggests that different countries contribute to global stability and competition in distinct ways.

Thus, I propose to the readers to consider this admittedly debatable, but largely empirically observable differentiation of roles as an alternative framework for understanding the international system:

A. The United States: Global Military Power and Hegemon in the Western Hemisphere

Since the end of World War II, the United States has positioned itself as the primary defender of the liberal international order. However, the viability of this role is increasingly under question. While Washington retains its military and financial dominance, its normative influence has declined in many parts of the world.

• The U.S. remains the world’s foremost military power, with extensive security commitments through alliances such as NATO, AUKUS, and the Quad.

• The dollar-centered global financial system ensures continued American influence over international trade and financial transactions, even as alternative currencies gain traction.

• The U.S.’s moral authority as a champion of democracy and human rights has weakened, particularly in the Global South, where many states view its foreign policy as increasingly transactional rather than values-driven.

• While U.S. commitments to defending Europe and deploying troops globally have diminished, its focus on consolidating influence over Mexico, Canada, Greenland, and Latin America has intensified (see the case studies analyzed below), which suggests a bid for establishing hegemonic presence across the Western hemisphere.

Thus, rather than serving as a guardian of the liberal order, the U.S. may increasingly be characterized as the dominant military power with an iron regional presence in the Western hemisphere within an evolving, structurally decentralized global system.

B. China: Champion of State-Led Economic Growth and Multipolarity

China’s success of sustaining rapid economic growth for four decades is unprecedented in world history. This economic modernization is a prime example of the achievements that can be reached on a large scale when the state actively engages in promoting development, rather than solely relying on neoliberal market principles.

• Through initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China has positioned itself as a leading force in global infrastructure development, particularly in the Global South.

• Beijing actively advocates for multipolarity, promoting a world where power is distributed across multiple actors rather than concentrated in a U.S.-dominated system.

Apart from the strategic aspect of growing Chinese influence in parts of Asia and the Pacific Ocean which concern the U.S. military strategists directly, from a global and systemic perspective, China’s challenge to U.S. leadership is not primarily military but economic and institutional, offering an alternative development model that appeals to many states seeking growth without Western-style political conditionality.

C. Russia: Disrupter and Returning Power

Russia’s current global role is more often disruptive than integrative. While it lacks China’s economic weight or America’s global military reach, it remains geopolitically significant due to:

• Its nuclear arsenal, ensuring its status as a top-tier military power.

• Its energy dominance, particularly as a major supplier of oil and gas to Europe, China, and other regions.

• Its revisionist policies, as seen in its territorial ambitions in Ukraine and efforts to reassert influence over former Soviet states.

Russia’s actions reflect an effort to restore parts of its geopolitical role, which was completely lost in 1989. Moscow is actively working to re-establish its sphere of influence, a process likely to continue—through diplomatic, economic, or military means—in the years ahead. During or after this process, ambitions for an alternative, more constructive, long-term role might begin to become more evident.

D. The European Union: Normative / Regulatory Power

The European Union presents a unique case in global politics. Although it has some military capabilities (e.g., nuclear power of Britain and France, as well as limited but still relatively well-prepared standing armies), it is not a global military power at the level of the U.S., China, or even Russia when one considers the latter’s nuclear arsenal. While there are ongoing calls for the rearmament of Europe (European Commission, 2025), at the time of writing this paper a more distinct form of influence from the region can be discerned in the areas of economic regulation and normative leadership.

• The EU has exported its regulatory frameworks to shape global standards, particularly in areas such as privacy laws (GDPR), trade policies, and environmental standards.

• Despite its regulatory power, Europe remains dependent on U.S. military protection through NATO, limiting its ability to act independently in security matters.

While the EU sees itself as a force for global governance, the extent to which regulatory influence constitutes true geopolitical power remains debatable.

E. India: Non-Aligned Regional Power with Strategic Autonomy

India remains one of the most strategically independent actors in global politics. It is a major regional power that does not align fully with any single geopolitical camp.

• India participates in U.S.-led initiatives like the Quad while simultaneously maintaining strong economic ties with Russia and a complex relationship with China.

• Its long-standing policy of non-alignment continues to shape its decision-making, making it an unpredictable yet pivotal player.

Given its growing economic and military strength, India is likely to emerge as a critical “swing state” in future geopolitical competitions, though its precise long-term role remains uncertain.

F. The Gulf States: Energy Powerhouses and Emerging Diplomatic Brokers

The Gulf states, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE, have traditionally derived their influence from control over global energy markets through OPEC. However, in recent years, their geopolitical roles have expanded:

• They have positioned themselves as diplomatic brokers, mediating conflicts in Sudan (Al Jazeera, 2023) and between regional actors, while also hosting talks between U.S. and Russian officials on Ukraine (Beaumont, 2025).

• Their increasing engagement with China, Russia, and BRICS suggests that they are exploring alternatives to traditional security ties with the U.S.

Though not yet full-fledged global mediators, the Gulf States are increasingly leveraging their economic power to shape diplomatic outcomes.

G. Brazil and South Africa: Spokespersons for the Global South

Brazil and South Africa occupy a unique position as representatives of the Global South, advocating for greater inclusion of developing nations in global governance.

• Both are members of BRICS, which has been expanding its influence as an alternative to Western-led institutions.

• They continue to push for reforms in international organizations like the UN, seeking a stronger voice for emerging economies.

• While neither country is a dominant global power, they play an important role in shaping discourse on multipolarity and development.

This analysis moves beyond traditional narratives of polarity in the international system. Instead, it offers a more nuanced understanding by examining the functional roles that different states and regions play, highlighting both the complexity of the global order and the contributions—as well as the limitations—of today’s major powers. One key implication of this arrangement is that, as long as states complement rather than directly challenge one another, a seemingly multipolar order may prove more stable than many realists would predict.

A globe in the process of fragmentation. Copyright-free image from Unsplash.

III. Foreign Policy under Trump 2.0: U.S. Strategic Repositioning?

12. Strategic Options for the United States in the New Global Order

However one chooses to describe the nature of the shifts in the international system and their outcomes, there is no doubt that they are taking place and reshaping the global order. In this context, the key question facing the United States is: What strategic approach should it adopt? Given the shifts discussed in previous sections, U.S. policymakers must decide whether to maintain global leadership, adapt to multipolarity, or retreat from certain international commitments.

To explore this question, I engage in an intellectual exercise by outlining, and then analyzing five distinct strategic options, drawing inspiration from various schools of IR. Each option a different vision for America’s role in the 21st century. This scenario-based approach allows to build and employ an analytical framework in times of continuous change and uncertainty. Beyond the scope of this paper, it could also be dynamically adapted to describe ongoing adjustments to the trajectory of U.S. foreign policy in the coming years.

“The World Turned Upside Down”, a sculpture by Mark Wallinger at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Copyright-free image by Mehmet Ali Eroglu from Unsplash.

Option 1: Reinforcing U.S. Primacy

The most ambitious strategy seeks to restore U.S. global leadership to its post-Cold War heights, ensuring that Washington remains the uncontested hegemon in international affairs. This approach requires:

• Reasserting U.S. dominance across all key regions through sustained military, economic, and diplomatic engagement.

• Containing geopolitical challengers, particularly China and Russia, to prevent them from reshaping global governance structures.

• Leveraging economic tools—such as sanctions and trade restrictions—to weaken rivals and reinforce American hegemony.

However, this strategy faces serious limitations. Maintaining primacy demands enormous resources, and overstretch has long been a recurring concern in American strategic thought. Moreover, the world has changed significantly since 1989, with rising powers and shifting alliances making a unipolar order increasingly unsustainable.

Option 2: Strategic Balancing (Selective Engagement)

A more pragmatic alternative is selective engagement, which seeks to maintain U.S. leadership in key regions while avoiding unnecessary overextension. This strategy would emphasize:

• Prioritizing the Indo-Pacific, with China as the primary geopolitical rival.