Citation (Harvard): Mballa, A. (2024) “Asynchronous Regional Integration in Central Africa: Progress and Challenges”, Regional Policy Insights, 2(1): 49-61.

Abstract:

This paper examines the uneven progress of regional integration within the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC). While integration has been a key objective in contemporary international relations, particularly in Africa, CEMAC’s member states face numerous obstacles, including governance issues, demographic disparities, and security concerns. The study highlights both positive developments, such as infrastructure projects and economic cooperation between Cameroon and Congo, and persistent challenges, such as border disputes, population imbalances, and the role of external actors in maintaining security. It argues that effective integration requires improved governance, strong institutions, and policies that address the socio-economic needs of local populations. Drawing comparisons to the European Union, the paper explores how CEMAC can overcome its challenges to deepen regional cooperation. Ultimately, the success of regional integration in Central Africa depends on both political will and sustained commitment to regional solidarity.

Keywords: regional integration, regional organizations, CEMAC, border disputes, Central Africa, economic cooperation, security, infrastructure, natural resources.

1. Introduction

In contemporary international politics, achieving deeper integration has become a key objective for many regions. While state sovereignty remains essential, its interpretation has evolved, particularly as countries begin to prioritize regional frameworks over national borders. This shift towards regionalism, often aimed at fostering economic, political, social, and cultural cooperation, is seen as a way to build stronger, integrated ties between groups of states. As Daniel and Nagar (2014) note, “region building is commonly defined as the efforts by states in a common region to cooperate in ways that enhance their political, economic, social, security, and cultural integration.” The European Union (EU) remains the most successful example of this evolution, operating through a system of independent institutions and intergovernmental cooperation.

It is unsurprising, then, that other regions, including Africa, have sought to emulate the EU’s model. Organizations such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the East African Community (EAC), and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) have made significant efforts towards regional integration. However, these efforts have faced considerable challenges. As Daniel and Nagar (Ibid., p. 10) point out, “in the five decades since the emergence of a pan-African ideology that sought the political emancipation of territories through regional integration, the results have been disappointing.” Only 12 percent of Africa’s trade is intra-regional, and historical divisions, institutional weaknesses, and fragmented economies have hampered regional cooperation.

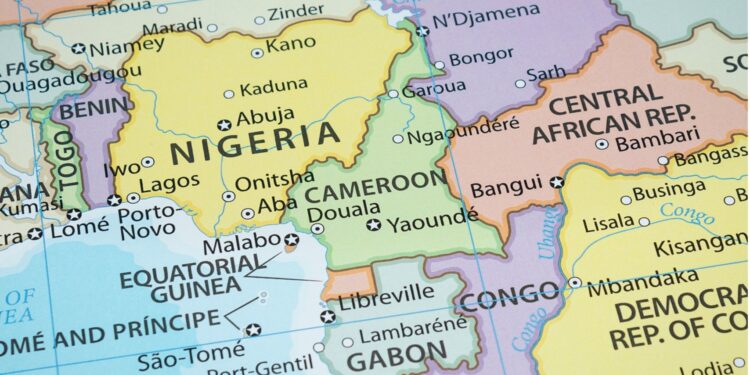

Despite these challenges, some progress has been made, particularly at the sub-regional level, with varying degrees of success. The Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC), established in 1994 and formalized in 1999, includes six member states—Cameroon, Chad, Congo, Gabon, Central African Republic (CAR), and Equatorial Guinea. These countries share a common currency, the CFA franc (XAF), backed by the French treasury at a rate of 655 XAF per euro. While efforts to promote regional integration, such as the 2017 agreement on the free movement of persons and goods, have been signed, practical implementation remains uneven (Martínez-Zarzoso, 2017).

Regional integration efforts often depend on a dominant member state. In CEMAC, Cameroon naturally assumes this role, given its economic strength and population size. In 2020, Cameroon’s economy represented 44.6% of CEMAC’s overall GDP, according to the Banque de France (2022). Despite this, the movement of goods and people between Cameroon and other CEMAC members remains restricted, as illustrated by recurrent border closures and disputes.

One example of these challenges is the relationship between Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea. Despite infrastructure projects linking the two countries, such as a road network connecting their capitals, Equatorial Guinea unilaterally closed its border with Cameroon ahead of its 2022 presidential elections (Africanews, 2022). In addition, following a failed coup attempt in 2018, Equatorial Guinea began constructing a border fence, exacerbating tensions with Cameroon. Although diplomatic negotiations eventually resolved the dispute, similar issues of trust and cooperation continue to plague regional integration efforts.

The issue of expulsions further complicates relations within CEMAC. Equatorial Guinea and Gabon frequently expel Cameroonians and other African nationals, citing irregular immigration statuses. In 2011, Gabon expelled 3,000 foreign workers, including Cameroonians, from a gold mining site (RFI, 2011). Equatorial Guinea’s expulsions have been more frequent, and reports of officials tearing up valid documentation of those expelled further strain relations.

Tensions are even more pronounced between Chad and the Central African Republic (CAR), two countries with long histories of political instability. Both states have served as bases for rebel groups operating across their shared borders, leading to violent clashes. In May 2021, six Chadian soldiers were killed, five of whom were allegedly captured and executed during a skirmish with CAR forces (France 24, 2021). Chad responded by reinforcing its military presence along the border, underscoring the fragile nature of regional security and integration in Central Africa.

2. Positive Developments in Central African Integration

Despite the challenges facing regional integration in CEMAC, there are notable positive developments. A key example is the cooperation between Cameroon and Congo. A recently completed highway now links their capitals, separated by over 2,000 kilometers. This infrastructure project quickly became a lifeline for business and travel. Unlike the recurring border issues seen between Cameroon, Gabon, and Equatorial Guinea, this road has sparked entrepreneurial activity. Two private coach companies now operate weekly trips between the capitals, offering a significantly cheaper alternative to air travel, with tickets costing approximately one-sixth of the price of a flight. Unsurprisingly, these trips often run at full capacity, as the highway opens up opportunities not only for commuters but also for cross-border trade.

The impact extends beyond Cameroon and Congo. Given that Brazzaville and Kinshasa are the world’s closest capitals, separated only by the Congo River, Cameroonians, particularly students in the DRC, now find it easier and more affordable to return home during holidays. Similarly, businesses have seized the opportunity to transport goods by land, circumventing the previously high costs associated with air or sea transport.

The integration between Cameroon and Congo is further bolstered by collaborative economic ventures. Both countries have agreed to jointly exploit the Mbalam-Nabeba iron ore deposit, located across their shared border (Nua, 2024). This represents a shift in sub-regional natural resource exploitation, moving away from the nationalistic approaches seen in the past. For instance, Gabon’s export of manganese and uranium historically relied on infrastructure connecting to Congo’s ports. Today, the plan to construct a railway from Nabeba in Congo to Cameroon’s Kribi deep seaport demonstrates a rational, economically efficient approach (Maritim Africa, 2024). This route offers a shorter, more cost-effective option than transporting resources to Pointe Noire in Congo, which is located over 1,600 kilometers away.

Additionally, the two nations have initiated the construction of a 600-megawatt hydraulic dam in Chollet, northern Congo, which is expected to meet the energy demands of both countries, as well as the Central African Republic (Takouleu, 2021).

This cooperation extends beyond infrastructure and economic projects. In the field of education, an interstate university has been established with its rectorate in Ouesso (Congo) and a campus in Sangmelima (Cameroon). Both cities are connected by the new highway, symbolizing the tangible benefits of integration in various sectors.

Moreover, there are no reported tensions between Cameroon and its southern neighbors—Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and Congo—which have fostered relatively friendly relations. Equatorial Guinea, for instance, is planning to relocate its capital to Oyala, a city located 150 kilometers from the Gabonese border, for security reasons. This move is designed to address vulnerabilities faced by the current capital, Malabo, located on an island. In a similar vein, the Bank for the Development of Central African States recently provided a $150 million loan to Equatorial Guinea for the construction of several projects, including a road linking the towns of Akurenam and Minang, with the goal of connecting the country to Gabon.

Relations between Gabon and Congo are equally positive, facilitated by the Okoyo-Lekety-Mbie highway, completed in 2014 (Gabon News, 2014). A new road under construction between Dolisie (Congo) and Ndende (Gabon) will further enhance connectivity between the two nations. Additionally, familial ties between the leadership of both countries—late Gabonese President Omar Bongo married the daughter of Congo’s current leader, Denis Sassou Nguesso—help solidify cooperation over confrontation.

Aside from these transnational road networks, other integration projects are underway. Cameroon and Chad are collaborating on an electricity interconnection program, leveraging Cameroon’s hydraulic potential. Optical fiber projects are also being implemented or planned between several nations, including Cameroon, Congo, Gabon, and the Central African Republic.

These examples of cooperation raise the question: Why is regional integration in Central Africa so inconsistent, and why do doubts remain about its effectiveness?

3. Challenges to Regional Integration in Central Africa

There is no single explanation for the inconsistencies in regional integration across CEMAC, but several factors offer insight. One key issue is the heterogeneity among member states. According to World Bank estimates from 2021, Cameroon has a population of 27.2 million, Chad has 17.18 million, Congo has 5.83 million, Gabon has 2.34 million, and Equatorial Guinea has 1.63 million. This demographic variation contributes to the differing approaches to integration, particularly regarding the movement of people and goods.

For example, while the smaller populations of Congo and Gabon are more readily accepted in Equatorial Guinea, the significant population disparity between Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea often leads to tensions, with Cameroonians perceived as “invaders.” The population ratio between Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea is approximately 16:1, compared to a 7:1 ratio between Nigeria and Cameroon. Despite hosting around 4 million Nigerians (Bonny, 2023), Cameroon does not resort to periodic mass expulsions, as seen in Equatorial Guinea. Additionally, the Minawao camp in northern Cameroon shelters thousands of Nigerians fleeing Boko Haram, and visa-free entry for short stays is reciprocal between the two nations.

Another challenge is the ratio of population to territory. Chad, for instance, has a population of 17 million spread over 1.28 million square kilometers, while the Central African Republic (CAR) has 5.45 million people in an area of 623,000 square kilometers. In contrast, Cameroon’s 27 million inhabitants occupy 475,000 square kilometers, and Gabon’s 2.34 million people inhabit 267,667 square kilometers. Equatorial Guinea’s small population is spread across just 28,051 square kilometers. Countries with lower population densities may find it easier to maintain effective control over their territories, while landlocked nations like Chad and CAR face greater challenges due to their geographical disadvantages.

Economic stability also plays a role in integration success. According to the African Development Bank’s Central Africa Regional Integration Strategy Paper (2019-2025), the Gross National Product (GNP) per capita varies widely among CEMAC member states. In 2010 US dollars, Cameroon’s GNP per capita was $1,503.53, Congo’s was $2,576.39, Gabon’s was $9,442.02, and Equatorial Guinea’s was $11,486.61. In contrast, Chad’s was $823.43, and CAR’s was just $335.02. There is a clear correlation between lower GNP per capita, high unemployment, and political instability, as poorer nations like Chad and CAR face greater challenges in maintaining domestic security and preventing youth from being co-opted by armed groups.

Security concerns also impede effective integration. In some cases, security issues take precedence over economic cooperation. Angela Meyer (2008) points out that increasing tensions in CAR led CEMAC to deploy a multinational force, the FOMUC, in 2002 to address regional security concerns—an action not originally foreseen in its treaty. While the economies of CEMAC member states are largely dependent on commodity prices, these nations also face the constant threat of instability spilling over from their neighbors, particularly from CAR.

A major obstacle to integration lies in the inability of some member states to control their entire territories. In CAR, the withdrawal of French and US forces in 2016 left vast portions of the country vulnerable to rebel control. According to Eric Benda’s (2020) research, before the Wagner Group intervened, up to 75% of CAR’s territory, including 12 of its 16 prefectures, was controlled by rebel groups.

The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (2022) reports that during an offensive between December 2020 and January 2021, CPC-aligned militias gained significant territory. In response, Wagner mercenaries were deployed alongside national and international forces. The inability of central governments to maintain territorial control allows rebel groups to move freely between countries, as seen in the ongoing tensions between Chad and CAR.

The lack of effective control can have severe consequences. For example, Chad’s late President, Marshal Idriss Deby Itno, was killed in a battle with rebel forces that had entered Chad from Libya, traveling hundreds of kilometers without encountering resistance (Marc, 2021). Similarly, in 2008, the French company Areva abandoned a 27 million euro uranium project in CAR due to rampant insecurity.

While external military support, such as Wagner’s involvement in CAR, may benefit regimes in the short term, it often comes at the expense of the broader population. The Wagner Group has been criticized for operating independently of state forces in at least 50% of political violence incidents in CAR since 2021. Despite decades of French and UN intervention, external forces have not been able to establish sustainable peace and security. The key question now is whether the current level of control can be maintained and whether it will lead to lasting stability both for CAR and the wider region.

4. Governance and Regional Integration in Central Africa

Decades of poor governance have significantly contributed to the current situation in countries like the Central African Republic (CAR). As Eric Benda (2020) highlights in his thesis, incompetence and irresponsibility in state affairs have led to widespread frustration and political and social unrest. Often, this incompetence stems from a lack of basic common sense. For example, in CAR, only Christian religious holidays, such as Christmas and Easter, are legally recognized, while Muslim religious events are celebrated informally.

Other issues, such as unauthorized access to public media by opposition parties, nepotism, and violations of the rule of law, exacerbate tensions. A notable example is the arrest and imprisonment of 73 individuals, including four deputies, in 2000, despite legal procedures requiring the removal of parliamentary immunity. This incident occurred under the democratically elected President Ange Felix Patassé, further fueling dissatisfaction.

The presidential elections of January 23, 2010, which had already been postponed twice, were another turning point. Many voters, waiting to cast their ballots, were surprised to be informed that the vote had ended five hours earlier, with the counting conducted overnight using candles and mobile phone flashlights. Although this may seem insignificant, such frustrations contribute to the radicalization of political parties, transforming them into armed rebel groups capable of overthrowing incumbent regimes.

After General François Bozizé won the 2010 election, Joachim Kokate, a member of the opposition party Convention des Patriotes pour la Justice et la Paix, openly called for the remobilization of dissident armed groups. The internal instability of a country, therefore, directly affects its ability to participate in regional integration efforts.

In CEMAC, regional integration has been marked by both achievements and setbacks. As Daniel and Nagar (2014) note, “weak states tend to generate weak regional organizations, and weak regional organizations are often unable to resolve the intra- and inter-state conflicts that generate weak states and undermine national institutions.” The effectiveness of regional integration in CEMAC since 2017 will depend on the ability of member states to implement policies that address the root causes of discontent and frustration within their populations. One of the primary grievances of rebel groups is the lack of inclusivity within incumbent regimes.

Additionally, countries like Chad and CAR face natural disadvantages as landlocked nations. The Kribi deep seaport in Cameroon and the Pointe-Noire deep seaport in Congo offer critical access to the sea, and the stability of Chad and CAR is closely tied to their cooperation with neighboring countries that have coastal access. The resolution of the dispute between Chad and Cameroon over the Chad-Cameroon pipeline is a positive step forward, but the main challenge remains ensuring that such cooperation benefits local populations.

In summary, states with similar characteristics are more likely to successfully implement regional integration within the CEMAC zone. The heterogeneity of CEMAC members, along with their internal situations, shapes the pace of integration. While some leaders recognize the advantages of integration, others see it as a threat. Nevertheless, CEMAC as an organization has made tangible progress. The Community Court of Justice and the Community Parliament are operational and complement existing institutions like the Conference of Heads of State and the Executive Secretariat.

While regional integration depends largely on the political will of heads of state, it is not unrealistic to believe that these institutions, through consistent practice, can give real meaning to integration within the sub-region. Most integration efforts in Central Africa have focused on the free movement of people and goods, with less emphasis on the well-being of local populations. For this reason, institutions like the Community Parliament and Court of Justice must take a leading role in protecting the rights of local populations, particularly in natural resource exploitation projects.

Unfortunately, as Boniface Sahinsou (2020) points out, this has not been the case in sectors such as mining in Cameroon. The need for land tenure reform in the context of resource extraction, as Koudama (2020) argues, is urgent, alongside other social and economic issues affecting the rights of populations in the CEMAC zone. By comparison, the European Parliament and its Court of Justice play a more effective role in guiding European integration than individual heads of state. A similar approach could help CEMAC achieve deeper and more meaningful integration.

5. Conclusion

The journey toward regional integration in Central Africa, particularly within the CEMAC zone, is one of significant complexity. While the promise of cooperation is evident, with infrastructure projects and economic partnerships leading the way, the realities of uneven governance, security concerns, and demographic imbalances present considerable obstacles. Countries such as Cameroon and Congo have shown that integration is possible when driven by mutual interests and a focus on economic rationality. However, countries like Chad and the Central African Republic, burdened by internal conflicts and geographical disadvantages, have struggled to fully engage in regional initiatives.

The effectiveness of CEMAC’s integration efforts will depend on the commitment of member states to address the root causes of discontent, improve governance, and ensure that regional policies truly benefit their populations. The role of institutions like the Community Parliament and the Court of Justice must evolve beyond merely facilitating free movement of goods and people to championing the social and economic rights of local populations. As the European Union’s experience has shown, successful regional integration requires both strong institutions and political will.

In the end, while the path to deeper integration in Central Africa remains fraught with challenges, the foundations laid by CEMAC provide a framework that, if built upon, could lead to a more interconnected and prosperous region. The key will be in overcoming both internal and external hurdles through cooperation, inclusive governance, and sustained commitment to regional solidarity.

References

African Development Bank (2019) Central Africa Regional Integration Strategy Paper 2019-2025. Available at: https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/documents/strategy-documents/central_africa_risp_2019-_english_version_020619_final_version.pdf

Africanews (2022) Closure of Equatorial Guinea’s Borders Impacts Cameroonian Traders. 13 August. Available at: https://www.africanews.com/2022/11/02/closure-of-equatorial-guineas-borders-impacts-cameroonian-traders//

Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (2022) Wagner Group Operations in Africa. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep42841

Banque de France (2022) CEMAC – Projections Macroéconomiques. Available at: https://www.banque-france.fr/sites/default/files/media/2022/06/30/cemac_cameroun2020.pdf

Benda, E. (2020) L’action de l’Union Africaine Dans Le Maintien De La Paix En Afrique: Cas De La République Centrafricaine. Doctoral Thesis, Université Catholique d’Afrique Centrale, Ecole Doctorale Droits de l’Homme et Action Humanitaire.

Bonny, A. (2023) Nigerians Living Abroad Yearn For Change After Elections But Remain Pessimistic. Anadolu Ajansı, 22 February. Available at: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/nigerians-living-abroad-yearn-for-change-after-elections-but-remain-pessimistic/2827588#

Daniel, R. and Nagar, D. (2014) Region-Building In West And Central Africa. Centre for Conflict Resolution. Available at: http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep05162.9

France 24 (2021) Chad Accuses Central African Republic of ‘War Crime’ After Attack on Outpost. Available at: https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20210531-chad-accuses-central-african-republic-of-war-crime-after-attack-on-outpost

Gabon News (2014) The Okoyo-Lekety Road Border To Gabon Is Now Operational. 16 December. Available at: https://m.gabonews.com/2/news/world-news/article/the-okoyo-lekety-road-border-to-gabon-is-now

Koudama, Z. (2020) La Propriété Foncière À L’épreuve De L’exploitation Des Industries Extractives Au Cameroun. Doctoral Thesis, Université Catholique d’Afrique Centrale, Ecole Doctorale Droits de l’Homme et Action Humanitaire.

Marc, A. (2021) The Death of Chadian President Idris Déby Itno Threatens Stability in The Region. Brookings Institution, 29 April. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-death-of-chadian-president-idris-deby-itno-threatens-stability-in-the-region/

Maritim Africa (2024) Launch Of The Integrated Development Project For The Avima, Badondo, Nabeba And Mbalam Iron Ore Mines, As Well As The Construction Of The Mbalam-Kribi Railroad And The Mineral Terminal At The Port Of Kribi. 3 January. Available at: https://maritimafrica.com/en/launch-of-the-integrated-development-project-for-the-avima-badondo-nabeba-and-mbalam-iron-ore-mines-as-well-as-the-construction-of-the-mbalam-kribi-railroad-and-the-mineral-terminal-at-the-port-of/

Martínez-Zarzoso, I. (2017) The Euro And The CFA Franc: Evidence Of Sectoral Trade Effects. CeGE Discussion Papers, No. 311, University of Göttingen, Center for European, Governance and Economic Development Research (CeGE), Göttingen.

Meyer, A. (2008) Regional Integration And Security In Central Africa: Assessment And Perspectives 10 Years After The Revival. Egmont Paper 25, Royal Institute of International Relations.

Nua, D. B. (2024) Cameroon, Congo Take Mbalam-Nabeba Iron Ore Project To Next Level. The Guardian Post Daily, 13 May. Available at: https://theguardianpostcameroon.com/post/2864/en/cameroon-congo-take-mbalam-nabeba-iron-ore-project-next-level

RFI (2011) Violente Expulsion De 3 500 Orpailleurs Étrangers Par Les Militaires Gabonais. 13 June. Available at: https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20110612-violente-expulsion-3-500-mineurs-militaires-gabonais

Sahinsou, B. (2020) Exploitation Des Ressources Naturelles Et Droits Des Populations Autochtones Au Cameroun. Doctoral Thesis, Université Catholique d’Afrique Centrale, Ecole Doctorale Droits de l’Homme et Action Humanitaire.

Takouleu, J. M. (2021) Cameroon-Congo: China’s CGGC Wins The Construction Of The Chollet Dam (600 MW). Afrik 21. Available at: https://www.afrik21.africa/en/cameroon-congo-chinas-cggc-wins-the-construction-of-the-chollet-dam-600-mw/

World Bank (2024) Where We Work. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/where-we-work

Fernand Guevara Mekongo Mballa is an Africa Fellow at the Centre for Regional Integration and a Doctoral Candidate at the Catholic University of Central Africa. He has published in the Journal of Law and Emerging Technologies and served as a Mentor for Cameroon for the Yale Young African Scholars Program between 2018 and 2021. Mballa is currently a Member of the Sabin Center Network of Rapporteurs on Climate Change at Columbia University.